The Networked Nonprofit of Tomorrow, Part 1: Ensuring Impact & Fundraising Success

January 24, 2017

This blog series unpacks and explores ONE HUNDRED’s recent findings on “networked nonprofits” and situates these hub-and-spoke entities’ unique organizational challenges in today’s philanthropic landscape.

Unique Challenges

“Networked nonprofits” operate as hub-and-spoke networks—with affiliates tied to a central headquarters—and represent a significant part of the nonprofit sector. These organizations face a unique mix of leadership, management, communications, and brand challenges—challenges that extend to fundraising and disbursement.

How funds are raised, how prospects are managed, how funds flow within a given network, and how transparency and accountability are established are all challenges that networked nonprofits face.

Definition + Scale

But let’s clarify what we mean by networked nonprofits. We use the term to refer to “hub-and-spoke” systems—any group of nonprofits with a central headquarters (which may be virtual) and distributed independent nonprofits that share the same brand and carry out a central mission at each of the affiliated sites.

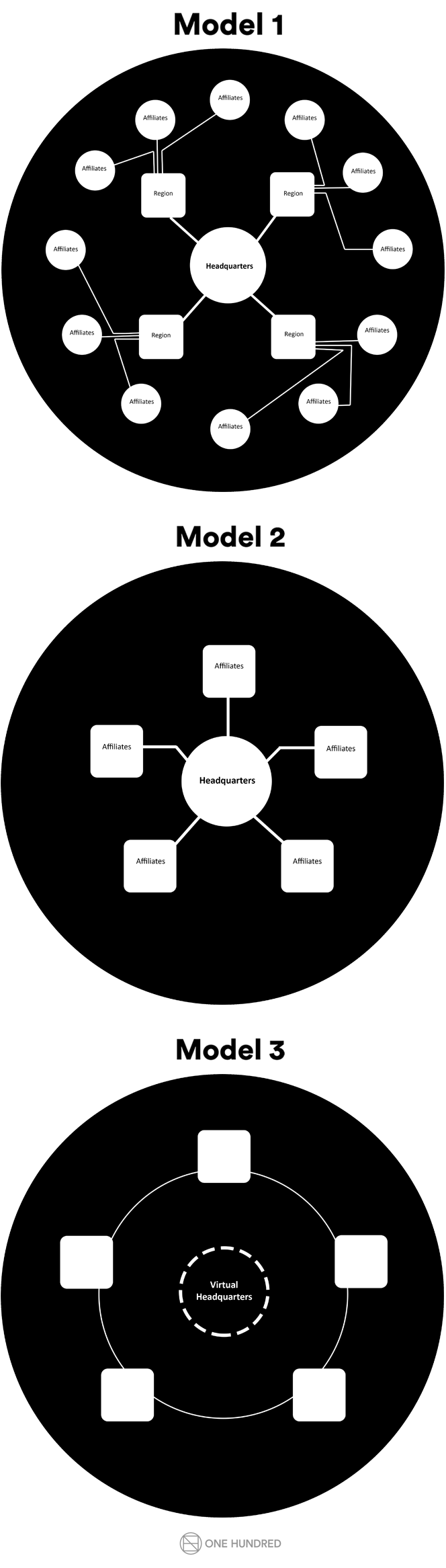

They are roughly of three types:

1. Layered networks in which affiliates are tied into regional organizations; and

2. Simple networks in which affiliates are tied directly into headquarters;

3. Virtual networks in which organizations sharing a brand and mission are tied together with only a virtual center.

“The key to fundraising success for networked nonprofits is a “positive sum” approach – the whole must be more than the sum of the parts.”

An analysis of these structures matters because affiliates are common in the nonprofit sector and often very large—roughly one fifth of the 400 largest U.S. nonprofits are networks whose annual revenues total nearly $50 billion: the YMCA system, Boys and Girls Clubs of America, Habitat for Humanity and the American Red Cross alone represent nearly 6,000 separately registered nonprofits, with the center representing anywhere between 22% and 80% of all funds raised in the system. Even smaller subsets of affiliate brands can represent huge numbers of autonomous but linked nonprofits. The scale is huge and the ways in which money moves are extremely varied.

(This rough measure markedly underestimates the scale and scope of networked nonprofits as it doesn’t take religious organizations into consideration, yet, many religious organizations are networks tied to a central authority.)

But all of these systems have similar problems in managing prospects, developing systems for the flow of funds from donors and outward to programs, and ensuring coherent and consistent communications and identity.

Ensuring Impact & Fundraising Success

Despite their inherent organizational challenges, the key to fundraising success for networked nonprofits is a “positive sum” approach—the whole must be more than the sum of its parts. Rather than being “zero sum”—what one part gains (the headquarters), the other loses (the affiliate)—the successful networked nonprofit will turn fundraising success at all levels into higher and higher levels of recognition, leadership and funding.

Having worked with dozens of networked nonprofits globally, ONE HUNDRED has identified five categories of issues that these organizations must address to lay the groundwork for success in today’s philanthropic market:

1. Transparency and Trust: Transparency between the center and the affiliate periphery is critical and turns on trust. The process for setting fundraising goals and holding all accountable for meeting those goals must be explicit, fair and transparent. The balance between demands from the center and consensus among affiliates is often difficult to strike, but system-wide participation and consultation is essential.

2. Common Metrics for Good Management: Efficiency is demanded by donors and is an expected characteristic of good management. The resources and systems at the center are usually greater than those at the periphery. This can create the perception of unfair goals driven by capacity at headquarters but not reality in affiliates. This can inhibit the affiliates’ ability to meet those goals. There is a critical need for common metrics across the organization and a willingness on headquarters’ part to make technical and personnel resources available to the affiliates to help meet goals.

3. Incentivize Prospect Sharing: Prospect market share is always a sticking point: Whose prospect is this? Who gets the credit? Who gets to count the gift against goal? The wisest nonprofits incentivize prospect sharing between affiliates and headquarters by sharing the application of gifts toward financial goals.

4. Clarity on Shared Performance Measurements: Tensions abound when it comes to measuring performance: programs feel fundraising isn’t meeting its needs; fundraising feels programs doesn’t understand what donors want; affiliates feel demands are excessive; headquarters feels no one is delivering on what’s needed to grow. The key? Shared clarity of expectations, shared reporting on organization-wide metrics, and proof of growth at all levels.

5. Balance Core Messaging with Local Flexibility: Consistency of external and internal communications is difficult for geographically disparate organizations. Brand erosion and donor confusion can be real threats when far flung affiliates try to adjust messaging to local needs, yet often that need can be very real in the eyes of local fundraisers. A shared central message with the flexibility to adapt to local needs is critical to successful fundraising for all networked organizations.

It is critical that networked nonprofits address these five categories to create balance between unity and autonomy in a way that drives fundraising success and promotes the perception of a strong national or international brand.

In our next post we will dive deeper into these challenges and explore different resolution tactics. We hope to see you then.

Download a PDF of this article here.